It is sometimes difficult to know the difference between God speaking and my own thoughts. But when God interrupts me, it’s obvious. That’s what happened in the middle of corporate worship on a Sunday morning in July. I experienced the Holy Spirit comforting me in the midst of anxiety, self-doubt, and impatience.

The feeling was the same as what I felt five years ago when I learned that my first child had died in the womb: despair, longing, and hope. Upon hearing confirmation of my son’s stillbirth, I was overcome by a strange and conflicting sense of sadness and hope—hope that I would yet know the joy of the Lord. And I did. I learned a great deal about joy in the midst of sorrow, pain, and longing.

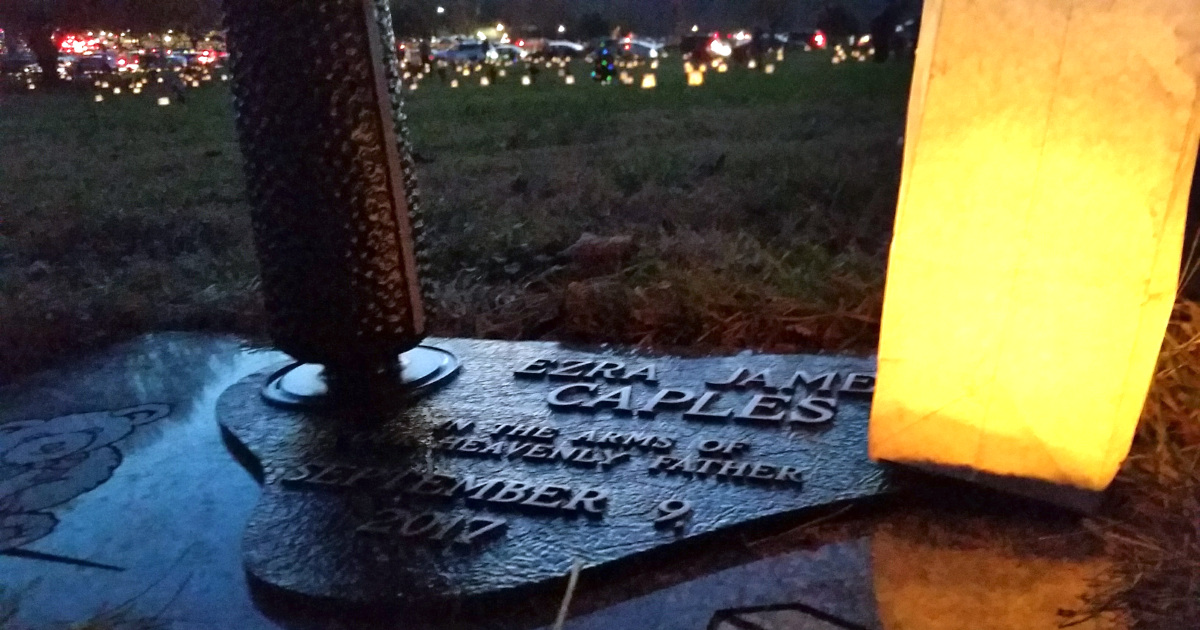

Losing Ezra James

That September day in 2017, as I paced the hospital room, waiting and hoping for a miracle for my unborn child, all I could do was pray. After more than two hours and several medical tests, my wife’s doctor walked in and confirmed the worst: there was no heartbeat; my son was gone. In the moments following, my mind briefly ran to panic, then immediately to sadness. Within a second or two of realizing that my son was dead, I heard a song playing in my head—frustratingly in the front of my grief-stricken mind. It was the song The Joy of the Lord, by Twila Paris, which we sang in my church growing up. It was the most perplexing song to hear at that moment, and I hated myself at the time for thinking of it. It was only a few hours later that I realized that the Holy Spirit had put that familiar song on my mind at just the right time to remind me that true joy isn’t dependent upon circumstances.

The joy of the Lord1—that peculiar, hope-filled, abiding, content-in-all-circumstances portion—is found in the dark places of our lives, when we come to terms with the reality that there’s no redemption on our own, no reconciling our own past or present or future, no walking out of the darkness ourselves, because it’s Jesus who redeems us, who saves us, is saving us, and will save us, and who carries us out of the darkest moments of our lives.

A small mercy from the loss of my son, Ezra James Caples, was that he was born perfect—without visible bodily damage. Not every angel2 has the same outcome. We get to treasure beautiful pictures of a baby who looks alive. As I held his lifeless body, I was overwhelmed with feelings of longing, despair, grief, anger. And joy. I kept thinking, This is my son, my child.

I couldn’t keep from smiling at my firstborn. I loved him so much at that moment.

Our entire church showed up at the funeral, and we sang The Joy of the Lord among the trees and grave markers in Nashville, Tennessee. It was a hot day for September, and the mosquitoes were hungry. But the biting sense of unfairness stung the most. Why did God give us so much happiness during the pregnancy months, only to take away our only child? Human suffering is a difficult topic and not one I’m attempting to address here, but I’ve learned to trust God and pursue joy in the wake of grief. God has been good to me, and I can’t say much more than that.

Anxiety

I’ve always dealt with social anxiety. I was a shy kid who never spoke up in class unless I was called on. (And being called on in class was terrifying.) I’ve been that way for as long as I can remember. I manage it better now, but I still feel tense around people I don’t know well.

Pushing grief aside

In February of 2018, I quit my job without another one lined up—uncharacteristic for me. It had only been five months since losing Ezra, but my wife suggested I quit the job I hated in order to take some time to grieve. We had also been doing grief counseling, which really helped me in many ways, one of which was realizing that I had been operating as if I hadn’t just experienced a loss. I had returned to work one week after my son’s stillbirth and, in many ways, acted like I needed to be strong for my wife—without taking time to grieve myself.

I also had some pent-up bitterness toward the people around me—my co-workers—for not responding to my grief in the ways that I thought I needed. It felt like none of them even cared about my pain. That was a very unfair burden to place on a group of people who really didn’t know me very well. And even if they had, grief manifests in ways that surprise even the griever. Another lesson from therapy: Most people mean well, but they still don’t know how to respond to someone else’s grief. I’ve found this is doubly true when people don’t know how to categorize a loss—like stillbirth.

Health fears

Later that month, I came down with a virus of some kind. I remember lying on the couch, struggling to breathe and seriously wondering if I would suffocate. We drove to the hospital, where I spent the next three days recovering from myocarditis, a condition marked by inflammation of the heart muscle. The viral infection had triggered an immune response in my heart. Though my heart wouldn’t give me any more real trouble after that (so far), I couldn’t shake the anxiety that had weaponized my diagnosis.

Fast-forward to 2020: The COVID-19 pandemic has been hard on everyone, in many different ways. 6.6 million deaths worldwide3, countless medical after-effects, relationships forever lost, abuse of all kinds on the rise, anxiety and depression skyrocketing. The toll is much larger than statistics can bear. And I was afraid for much of the pandemic—for my health, for my wife and living child4, and for my job.

I’ve spent the last few years struggling with anxiety about my heart health, my family’s health, my job, the global pandemic, and other concerns. Anxiety can be hard to shake. It’s not logical, and you can’t reason your way out of it—at least I haven’t.

Jesus, friend of the anxious

After years of silence from God—or more likely, closed ears on my part—he spoke to me in an elementary school gym as the congregation sang. But it wasn’t words that were communicated, only a feeling of comfort, as if El Roi, the God who sees, were wrapping me in his arms and whispering, I’ve got you.

It was simple and not particularly profound, but I couldn’t hold back my tears.

The sermon that day was on Psalm 25, an acrostic poem by David. In this psalm, David appeals multiple times to God to save him from his sins and his enemies. As in many of his psalms, David seems very anxious, recognizing the very real dangers of both his sinfulness and the malice of his enemies. Three times he mentions waiting for Yahweh (vv. 3, 5, 21). The transliterated word for wait

here is qavah (קָוָה), which connotes both waiting and hoping. But the hope is not simply wishing for something to happen; it’s waiting in expectation that it will happen. David’s hope in the Lord is an expectation of his salvation.

I believe it’s the same with anxiety. I’m waiting on the Lord and hoping in his promise of deliverance.

Turn to me and be gracious to me,

for I am alone and afflicted.

The distresses of my heart increase;

bring me out of my sufferings.Psalm 25:16–17, CSB

“Don’t worry”

I grew up believing that anxiety is sinful, but I don’t think it’s that simple. In Matthew 6, Jesus teaches us not to worry (be anxious

) about our lives (vv. 25–34), but I think this is more a comfort than a command. Consider how he illustrates the Father’s care for the birds (v. 26) and the wildflowers (vv. 28–30). Our heavenly Father knows our needs (v. 32), and he provides for his creation—the same creation over which humanity has dominion (Genesis 1:26). How much more, then, will he provide for his beloved children? Jesus offers comfort to those afflicted with anxiety, worry, and fear. Therefore don’t worry about tomorrow, because tomorrow will worry about itself. Each day has enough trouble of its own.

(v. 34) Truly, his yoke is easy and [his] burden is light.

(Matthew 11:30).

Matthew 6:25–34 is directly linked to the preceding verses (19–24). This passage isn’t just about greed and material wealth. When we fix our eyes on anything but Jesus, our treasure in heaven,

the instability of those things will inevitably lead us into anxiety. For our eyes to be healthy, we must look to the Light, not gaze into the darkness and wonder about the security of our health, beauty, intelligence, wealth, relationships, and abilities.

People who say, Jesus never had anxiety

have not closely read Luke 22, when Jesus sweated blood while praying in anguish

in the Garden of Gethsemane5 (vv. 39–466). Sweating blood is actually a very rare condition called hematidrosis that can be caused by intense stress. Jesus, knowing his destiny, was very anxious about going to the cross. He understands our anxieties and fears. Therefore, let us approach the throne of grace with boldness, so that we may receive mercy and find grace to help us in time of need.

(Hebrews 4:16, CSB)

One could argue that being under intense stress for a few hours is not the same as prolonged anxiety—it’s not—but Jesus experiencing anxiety, even briefly, is enough to establish that, not only is anxiety not sinful, it’s also common. I hope we can find some comfort in that. Jesus, being without sin,

(Hebrews 4:15)7 could not have experienced anxiety if it were a sin to do so. More than that, he understands our struggles with anxiety. Your fears and worries are not sinful, but Jesus still calls us away from the yoke of anxiety. I choose to believe it’s possible, even if incredibly difficult, to unburden ourselves from chronic worry, stress, anxiety, and fear.

I’m not there yet, though.

Learning to listen—and talk

After moving away from the community that loved us well, at quite possibly the worst time to relocate—December of 2019—I’ve spent the last three years disconnected. I’ve realized that I’m not quite as introverted as I thought, and I need to listen to my own longing for connectivity. I work from home in a quiet suburban neighborhood, doing mostly solo work, in a city where I still know very few people. It can be lonely, which is why I’m once again pursuing therapy.

At the time of writing, my anxiety is much less of a burden—for now. (Thank you, Wonderful Counselor!) I’m not a mental health expert by any means, and I don’t intend to suggest that prayer is a guaranteed prescription for anxiety. It’s not. But prayer is a crucial component in my personal anxiety journey, along with therapy8 and attention to my personal and interpersonal needs. Daily prayer, good nutrition, regular exercise, keeping caffeine in check, professional counseling, social presence, recreation. These are all ways that I’ve found to meaningfully cope.

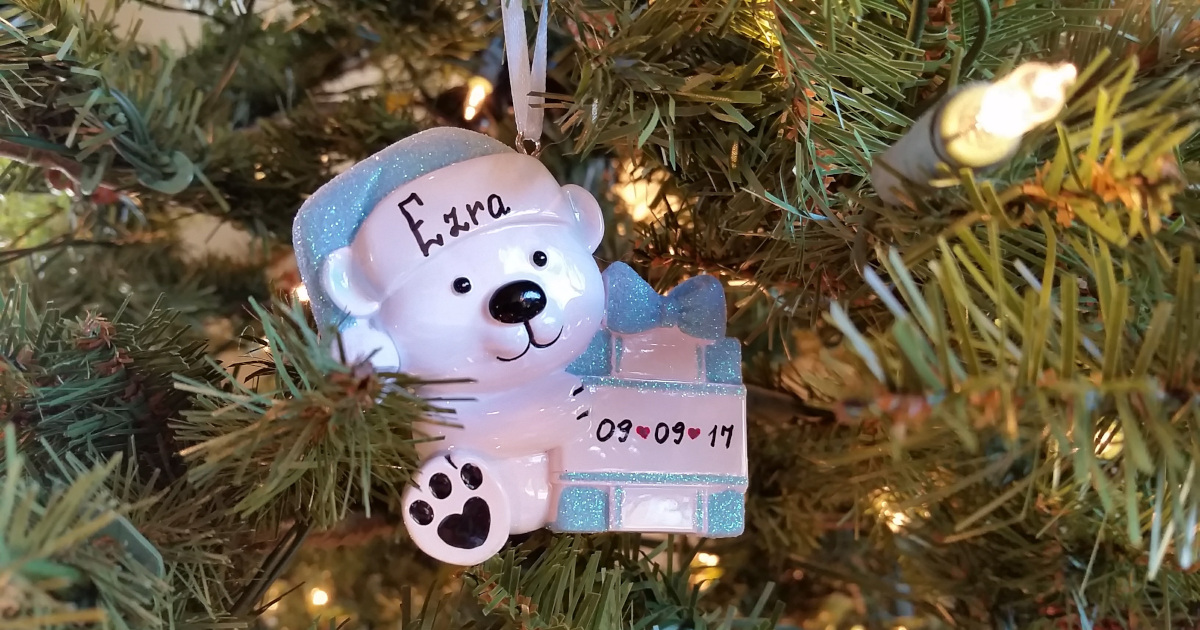

My social anxiety is not gone, though some of my other worries are. And I still miss Ezra; I hung his ornament on our Christmas tree yesterday. There are fewer triggers for my grief now, but the holidays can still be heavy. Christmas is joyful, fun, and spiritual, but the season still reminds me that I have two children, and only one of them can eat his gingerbread house face-first, hum Christmas music while decorating the tree, and cuddle up to holiday cartoons.

But I feel more hopeful than ever.

-

Nehemiah said,

(Nehemiah 8:10, NIV) ↩Go and enjoy choice food and sweet drinks, and send some to those who have nothing prepared. This day is holy to our Lord. Do not grieve, for the joy of the Lord is your strength.

-

“Angel” is the term used for babies lost during or immediately after pregnancy. ↩

-

Source: World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019. Accessed 4 December 2022. ↩

-

Our second child, also a boy, was born almost two years after Ezra, in July of 2019. ↩

-

The garden was at the base of the Mount of Olives, part of a Judean mountain range separating Jerusalem from the wilderness. ↩

-

This story is also found in Matthew 26:36–45 and Mark 14:32–42, and it’s referenced in John 18:1. ↩

-

See also Romans 5:12, 8:3; 2 Corinthians 5:21; Hebrews 7:26, 9:14; 1 Peter 1:19, 2:22; 1 John 3:5. ↩

-

As of December 2022, I’m trying to get an appointment with a therapist in a non-virtual session who will accept my insurance. ↩