In The Unseen Realm, Michael S. Heiser conveys not only the reality, but also the significance of supernaturalism in Scripture. The biblical authors possessed a supernatural worldview that included belief in many elohim—non-physical spiritual beings. Yahweh has always been the Lord of Lords, the Creator, the Supreme Elohim. But there are a host of others beyond angels, the messengers of God.

Like Heiser, my journey of discovery with the supernatural worldview of Scripture began with Psalm 82. It’s an easy psalm to overlook, but Jesus himself references this “problem passage” during his ministry.1 Psalm 82 begins like this:

God [elohim] stands in the divine assembly;

he administers judgment in the midst of the gods [elohim].Psalm 82:1, LEB

The second use of the Hebrew word elohim is rendered plural. Modern Western society has rather specific ideas of what a “little G” god is—mostly an ancient mythical concept such as Zeus, Krishna, Osiris, Molech, or Odin—with powerful, yet limited, capacities for creation, manipulation, and destruction. Throughout human religious history, popular beliefs usually centered on a pantheon of gods who worked together and sometimes fought each other. This book explores the idea that the Bible itself might support the existence of other deities—just not in the ways we’ve always considered them.

As strange as this book may seem to Western Christians, the author has collected thousands of books and scholarly articles from which he has gleaned his knowledge of the subject. He assures the reader that the contents of this book have passed scholarly peer review; he’s not making things up. Heiser also ensures both accessibility and clarity of the ideas presented in The Unseen Realm by offering another book2 for those who find this one too dense, and a companion website3 for those who desire more information—a deeper dive.

The mosaic of Scripture

Heiser uses two metaphors to describe his Bible study experience before and after his “Psalm 82 moment”: a filter and a mosaic. Filtering is a common practice of Western Christians when we study our Bibles. We use our modern-day, present-culture beliefs and biases to inform our understanding of Scripture, rather than attempting to interpret the Bible through the lenses of the biblical authors themselves. What did Moses, Ezra, David, Isaiah, Ezekiel, Daniel, the gospel writers, Paul, and Peter believe when they wrote their portions of inspired Scripture, and how did those beliefs inform their writing?

The second metaphor, a mosaic, describes Heiser’s perspective of Bible passages as individual pieces that together complete a beautiful mosaic.

The Bible is really a theological and literary mosaic. The pattern in a mosaic often isn’t clear up close. It may appear to be just a random assemblage of pieces. Only when you step back can you see the wondrous whole.

Michael S. Heiser, The Unseen Realm

Heiser asserts that these individual pieces are data points that can tell a bigger story when put together. He even identifies several problem passages

4 that often get left out of sermons because they’re simply too confusing or strange. The serious Christian should strive to remove their filter and take up the task of piecing together the mosaic of Scripture.

Obstacles

The obstacles to removing one’s filter and seeing Scripture as a mosaic are identified as the following: (1) thinking that Christian history is the true context of Scripture, (2) being desensitized to the theological significance of the unseen world, and (3) assuming that problem passages

are too odd to matter.

“The proper context for interpreting the Bible is the context of the biblical writers—the context that produced the Bible. Every other context is alien to the biblical writers and, therefore, to the Bible.”

Spiritual beings

Job is a fascinating book of profound theological importance. One significant mosaic piece found in this book is in Job 38:7, when God asks Job, rhetorically, if he was present at the creation. In relation to God laying the foundations of the world, the text reads, …when the morning stars were singing together and all the sons of God shouted for joy?

(LEB, emphasis added)

The sons of God (beney elohim) are divine beings with higher-level responsibilities or jurisdictions.

These same heavenly beings are also identified as morning stars. The original morning stars, the sons of God, saw the beginning of life as we know it—the creation of earth.

So these sons of God in high heavenly positions were with God before the creation of the universe.

Michael Heiser believes that the sons of God are referenced in Genesis 1:26 when God announces, Let us make mankind in our image, in our likeness…

(NIV) I have to admit that Heiser makes a compelling case, though I’ve long believed that the plurality of Genesis 1:26 refers to the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.5 But the author and readers of Genesis 1 would not have been familiar with the trinitarian nature of God, though he has always existed as such (John 1:1–2). Furthermore, Job 38:7 makes it clear that spiritual beings existed before the creation of the earth. Heiser writes later chapters under the assumption that the sons of God (spiritual beings) are God’s imagers in the heavenly realm, while humans are his imagers on earth.

| Hebrew (transliterated) | English meaning | Scripture (not comprehensive) |

|---|---|---|

| elim, elohim | gods, spiritual beings | Genesis 3:5, 22; Psalm 82:1, 5, 6; Ezekiel 28:2 |

| beney elim, beney elohim | sons of God, morning stars | Job 38:7; Psalms 29:1, 89:6; Isaiah 14:13; Ezekiel 28:13 |

| kokebey boqer | stars of God | Job 38:7 |

| adat, sod, mo’ed, moshab | assembly, council, meeting, seat (the divine assembly) | Psalms 82:1, 89:7; Isaiah 14:13; Ezekiel 28:2 |

| mal’ak | angels, messengers | Genesis 16:7–11; 19:1; 21:17; 48:16; Exodus 3:2; Numbers 20:14–16; Deuteronomy 2:26; Joshua 6:17, 25; 7:22; Judges 2:1–4; 5:23; 6:11–12, 20–22, 35; Nehemiah 6:3; Job 1:14; 4:18; 33:23; Psalms 34:7, 35:5–6, 78:49, 91:11, 103:20, 104:4, 148:2; Proverbs 13:17; 16:14; 17:11; Ecclesiastes 5:6; Isaiah 14:32; 18:2; 30:4; 42:19; Jeremiah 27:3; Ezekiel 17:15; 23:16, 40; 30:9; Hosea 12:4; Nahum 2:13; Haggai 1:13; Zechariah 1:9, 11–14, 19; 2:3; 3:1, 3, 5–6; 4:1, 4–5; 5:5, 10; 6:4–5; 12:8; Malachi 2:7; 3:1 |

| nachash | serpent (n), to use divination (v), bronze/brazen (adj) | Genesis 3, 49:17; Exodus 4:3, 7:15; Numbers 21:7,9, 23:23; 2 Kings 21:6; 2 Chronicles 33:6; Job 26:13; Isaiah 27:1, 65:25; Daniel 2:32, 4:15,23 |

| moshab elohim | “seat of the gods” (place of divine assembly) | Ezekiel 28:2 |

| shedim | demons | Deuteronomy 32:17 |

| kokebey el, helel ben-shachar | shining one, son of the dawn | Isaiah 14:12; Ezekiel 28:13 |

| rephaim | the dead in the underworld | Isaiah 14:9; Ezekiel 28:17 |

| daimōn/daimonion | devils, demons | Matthew 8:16, 20; 10:1; 12:43–45; 25:41; Luke 4:41; James 2:19; Ephesians 6:12; Revelation 12:7–9; 16:14 |

| nephesh/ruach | soul/spirit | Genesis 1:30; 1 Samuel 1:15; Job 7:11 |

Misinterpreting Psalm 82

The Hebrew writers of the Old Testament were not polytheists, though passages like Psalm 82 can understandably lead to that conclusion without an ancient Near Eastern worldview.

The plural use of elohim is not referring to the Trinity

It’s bizarre that some people have interpreted the second use of the word elohim in Psalm 82 to refer to the other persons of the Trinity. Heiser correctly calls this view a heresy. God is judging the elohim for corruption and sentences them to die like humans. None of this fits with God the Son or God the Holy Spirit.

Divine beings are not human

Some people believe the elohim to be Jewish humans, but Heiser points out the flaws in this theory. First, the Bible does not teach that Jewish people were put in positions of authority over other nations. In fact, they were supposed to be separate from other nations and peoples.

The covenant with Abraham presupposed this separation: If Israel was wholly devoted to Yahweh, other nations would be blessed (Gen. 12:1–3).

Second, humans are not disembodied, which is the definition of elohim—they are non-physical spiritual beings. Third, other biblical references to elohim place them in the heavens, not on earth.6

The ancient Israelites were not polytheistic

Unlike some biblical scholars, Michael Heiser does not believe that ancient Israel began as polytheistic and then adopted monotheism. The reason is simple: elohim does not mean God, but spiritual being. God and elohim do not share a one-to-one relationship. There is a hierarchy of elohim, with Yahweh at the top as the Almighty. Biblical authors did not always write the word elohim and think of Yahweh. There are several uses of elohim throughout the Bible:

- Yahweh, the one God of Israel (Genesis 2:4–5; Deuteronomy 4:35; thousands of other references)

- The divine council (Psalm 82:1,6)

- Deities of other nations (Judges 11:24; 1 Kings 11:33)

- Demons (Deuteronomy 32:17)

- Samuel, deceased (1 Samuel 28:13)

- Angels, Angel of Yahweh (Genesis 35:7)

Would any Israelite, especially a biblical writer, really believe that the deceased human dead and demons are on the same level as Yahweh? No. The usage of the term elohim by biblical writers tells us very clearly that the term is not about a set of attributes.

Michael S. Heiser, The Unseen Realm

The biblical authors assign unique attributes to Yahweh:

- All-powerful, omnipotent (Jeremiah 32:17,27; Psalms 72:18, 115:3)

- Sovereign king over other elohim (Psalm 95:3; Daniel 4:35; 1 Kings 22:19)

- Creator of the divine council (Deuteronomy 4:19–20, 17:3, 29:25–26, 32:17; Job 38:7; Psalm 148:1–5; Nehemiah 9:6; James 1:17)

- Only elohim deserving worship (Psalm 29:1)

Polytheism connotes the idea that a pantheon of gods are interchangeable and possess the same attributes, such as omnipotence.7 Though the nation of Israel frequently turned away from Yahweh to other gods throughout the Old Testament, the Israelites did not start as polytheistic, nor were they polytheistic by identity.

Are the elohim real?

For those who look at Psalm 82 and argue that the gods mentioned are only idols, Michael Heiser points to Deuteronomy: They [the Israelites] sacrificed to demons [shedim], not God [eloah], to gods [elohim] whom they had not known.

(32:17) Heiser handles this passage in greater detail in another article.8

In the context of Deuteronomy 32:17, shedim9 were elohim—spirit beings guarding foreign territory—who must not be worshiped.

Heiser contends that the elohim mentioned in the Bible are very real. The apostle Paul thought so, too. In his first letter to the Corinthians10, he warned the people of God not to fellowship with demons, using the Greek word daimonion to translate the Hebrew shedim in Deuteronomy 32:17. The demons referenced are rebellious spiritual beings in positions of power over other nations. But the Israelites must only worship Yahweh.

Even when Scripture says something like, There is no other god besides [Yahweh],

the meaning is that no other being compares to God, not that God is the only spiritual being. Remember that elohim (“god/gods”) refers to spiritual beings.11

The denial that other elohim exist insults the sincerity of biblical writers and the glory of God. How is it coherent to say that verses extolling the superiority of Yahweh above all elohim (Psa 97:9) are really telling us Yahweh is greater than beings that don’t exist? Where is God’s glory in passages calling other elim to worship Yahweh (Psa 29:1–2) when the writers don’t believe those beings are real?

Michael S. Heiser, The Unseen Realm

Idolatry

Ancient people did not consider idols to be their gods, as many modern Christians believe they thought. Rather, in ancient religious thought, idols were physical habitations for non-physical spiritual beings. Wood and stone idols were vessels for communicating with the deities and providing worship. As John H. Walton notes in his commentary on Genesis, the deity’s work was thought to be accomplished through the idol.

12

In fact, the third commandment against idolatry follows the second commandment against worshiping other gods. Why would God provide two “repetitive” commands? Because in ancient Near Eastern thought, the idol was only a way to communicate with the elohim. There is one command against worshiping other gods and another command against using idols, even in worship of Yahweh. God never wanted idols for himself. Rather, God created human beings to be his image on earth. We are the vessels!

Jesus the “only begotten son”

Since Jesus is called the only begotten son of God

by the apostle John13, what are we to do with the other sons of God

in the Bible? Is Jesus the only son of God or not? The Unseen Realm offers an explanation: a mistranslation of the Greek word for begotten, μονογενής (monogenes). Translating this word as only begotten

is problematic for two reasons—first, it contradicts other passages in the Bible that clearly indicate other sons of God, and second, it suggests that Jesus had a beginning, a birth.

The confusion extends from an old misunderstanding of the root of the Greek word. For years monogenes was thought to have derived from two Greek terms, monos (“only”) and gennao (“to beget, bear”). Greek scholars later discovered that the second part of the word monogenes does not come from the Greek verb gennao, but rather from the noun genos (“class, kind”). The term literally means “one of a kind” or “unique” without connotation of created origin.

Michael S. Heiser, The Unseen Realm

The logic of this translation is further supported by a New Testament reference to Isaac as Abraham’s monogenes.14 Isaac, of course, was not Abraham’s only son15, but rather his unique son—the son of the covenant promise through whom Messiah would come to save his people. Just as Yahweh is an elohim, and no other elohim are Yahweh, so Jesus is the unique Son, and no other sons of God are like him.

All humanity in relationship with Yahweh

In the first few chapters of the Bible, there is no Israel, only humanity, and God dwells with his first people in the garden of Eden. But it doesn’t take long for things to go wrong. In Genesis 3, Adam and Eve sin and are expelled from paradise. In Genesis 6, God sees that most of humanity is wicked; even God’s own heavenly children16 (spiritual beings) turn their backs on him to pursue human women. By chapter 11, God’s relationship with humanity at large reaches its tipping point with the tower of Babel.

As Richard Elliott Friedman notes in his Commentary on the Torah, Moses could have begun Scripture (Torah) with Exodus 12, when the people of Israel received their first commandment: to observe Passover. But crucial to Israel’s reception of God’s commandments is the knowledge of who God is and by what authority he commands the people. Friedman credits Rashi with this insight, but he goes on to remark that the first eleven chapters of Genesis depict the formation of a relationship between the creator and all the families of the earth.

17 Genesis begins with God in relationship with humanity, not just with Israel. This is the backdrop for the entire Old Testament.

The fall of humanity in the garden of Eden

There is no god like Yahweh. His goal of making the earth a new Eden will not be overturned.

(Michael S. Heiser, The Unseen Realm)

The garden of Eden was an idyllic place for the first people to live. Adam and Eve bore the responsibility of caring for—and enjoying—the garden, and they enjoyed regular fellowship with Yahweh there. Eden was the earthly home of the heavenly God. As Heiser notes, Yahweh was embodied among Adam and Eve in the garden, walking in the garden and speaking to them.18 But everything changed when Adam and Eve sinned by disobeying God after being tempted by the serpent to eat of the forbidden tree of knowledge of good and evil.

The fall of humanity in Genesis 3 is a simple story about a talking serpent—right? Not so fast, says Michael Heiser.

One of the first questions a reader of Genesis 3 might have is, “Why wasn’t Eve afraid of a talking snake?” Heiser believes questions like this preserve an overliteralized view of the text.

To the ancient Hebrew reader, the serpent is clearly a divine figure. After all, the garden of Eden is where heaven and earth meet—the earthly realm of the heavenly council. No citizen of an ancient Near Eastern culture would have believed that animals could talk in everyday life, but when the gods or magical forces were in view, that was a different story.

Animals often represented divine presence in ancient literature, and the kind of animal in a story typically depended on the attributes or status of that particular animal.

Genesis telegraphed simple but profound ideas to Israelite readers: The world you experience was created by an all-powerful God; human beings are his created representatives; Eden was his abode; he was accompanied by a supernatural host; one member of that divine entourage was not pleased by God’s decisions to create humanity and give them dominion. All that leads to how humanity got into the mess it’s in.

Michael S. Heiser, The Unseen Realm

The serpent in the garden of Eden

One of the most popular subjects of mockery for unbelievers is the talking snake in the opening story of Scripture. How ridiculous it is to believe anything in a book that opens with talking animals tricking the first people into sinning! But there’s much more to Genesis 3.

Heiser begins by addressing a defense of biblical literalism which posits that perhaps snakes could walk and talk during that time period. There’s even an evolutionary defense which claims that snakes once had legs.19 It’s a bit misguided when someone attempts to defend biblical literalism by appealing to the evolutionary history of snakes.

The point of the passage is not zoology anyway. Eve wasn’t afraid of the talking serpent because she (and the ancient reader of Genesis) understood that the garden of Eden was at the center of a Venn diagram of heaven and earth. She knew she was dealing with a divine being, and so did the ancient Near Eastern reader.

Another point about the serpent’s curse is that he was doomed to crawl on the ground and eat dust

all his days. The divine status of the serpent should alert us to the fact that this curse is not about snakes of the animal kingdom. According to Michael Heiser:

The Hebrew word translated “ground” is ’erets. It is a common term for the earth under our feet. But it is also a word that is used to refer to the underworld, the realm of the dead (e.g., Jonah 2:6), where ancient warrior-kings await their comrades in death (Ezek 32:21, 24–30, 32; Isa 14:9).

(Michael S. Heiser, The Unseen Realm)

It becomes clearer and clearer that the serpent’s curse was not about snakes crawling on the ground in the dust. It’s about a rebellious heavenly council member being cast from the heavenly realm to the underworld.

The prince of Tyre

Ezekiel 28, though not specifically about the fall of humanity, is conceptually linked to Genesis 3. In this passage, God accuses the prince of Tyre of incredible arrogance: he considers himself to be a god—a sin that must be punished. Yahweh tells the prince, You will die the death of the uncircumcised by the hand of strangers,

(28:10, LEB) a reference to Sheol, the place where the uncircumcised warrior-king enemies of Israel find themselves.

20

So where’s the link to Genesis 3? In the details, specifically those found in verses 12–17. Though the language of these verses conveys royalty and verse 13 mentions Eden, Heiser believes Ezekiel is not comparing the prince to Adam, the fallen priest-king of the garden, but rather to the divine being represented as a serpent (nachash).

The “prince” of Genesis 3 was beautiful and adorned with gemstones. He was an anointed guardian cherub

on God’s holy mountain.

He was consumed by his own beauty. He walked among stones of fire

(a reference to both the place and members of the divine council). None of this points to Adam; it all points to the serpent, a member of Yahweh’s divine council.

Heiser admits that this specific use of typology is not conclusive, and since a lot of its understanding rests on knowledge of ancient semitic languages, I find myself not fully grasping the concepts. But the comparison is interesting to say the least.

The disinheriting of the nations

In chapters 14–15 of The Unseen Realm, Michael Heiser pays special attention to the tower of Babel narrative, in which the people, sharing one language, set out to make a name for

themselves by building a city and a tower to reach the heavens—attempting to bring themselves back into Edenic paradise by their own power. In addition to the arrogance of attempting to make a name

for themselves by building their way to paradise, the people were also congregating in one place rather than spreading across the face of the earth as they were instructed by Yahweh.21

Because of the willful disobedience of the people, Yahweh confuses their language, scatters them across the earth, and apportions them to lesser elohim. God disinherits the humans he created, resolving to create a new nation from one man, Abraham. Deuteronomy 32:8–9 is a key verse when illustrating the disinheriting of the nations.

Deuteronomy 32:8–9 describes how Yahweh’s dispersal of the nations at Babel resulted in his disinheriting those nations as his people. This is the Old Testament equivalent of Romans 1:18–25, a familiar passage wherein God ‘gave [humankind] over’ to their persistent rebellion. The statement in Deuteronomy 32:9 that ‘the Lord’s [i.e., Yahweh’s] portion is his people, Jacob his allotted heritage’ tips us off that a contrast in affection and ownership is intended. Yahweh in effect decided that the people of the world’s nations were no longer going to be in relationship to him. He would begin anew. He would enter into covenant relationship with a new people that did not yet exist: Israel.

Michael S. Heiser, The Unseen Realm

Though most English translations of Deuteronomy 32:8 read, according to the number of the sons of Israel,

Heiser gives two reasons why the correct reading is, according to the number of the sons of God.

First, the Dead Sea Scrolls have clarified that the older manuscripts use sons of God. Second, the event at Babel occurs before the people of Israel existed.

The number 70 (or 72?)

Most students of the Bible know that certain numbers have special significance in Scripture. One of the numbers that comes up in both Old and New Testaments is 70. The religious significance of this number originates in Ugarit and Canaan with the worship of El, Baal, and Asherah. The Canaanite divine council was said to have 70 sons, so when Yahweh disinherited the nations at Babel—70 in all22—they were given over to other gods (i.e., spiritual beings) to be ruled by them, and a clear theological message was presented:

When Yahweh disinherited the nations and allotted them to the sons of God, a theological gauntlet was thrown down: Yahweh alone commands the nations and their gods. Other gods serve him.

Michael S. Heiser, The Unseen Realm

Following the events at Babel, Exodus 18 and 24 record 70 elders who govern Israel and even see the God of Israel

from a distance (24:10). With Moses as the leader, Israel is governed by a council of 70 elders. That leadership structure extends into the New Testament with the Sanhedrin, a 70-member governing body led by the high priest.

During his ministry, after empowering the twelve apostles to cast out demons in his name, Jesus sent 70 other disciples to the local towns he was about to visit.23 He gave them the power to heal and cast out demons in his name. They return and exclaim, Lord, even the demons submit to us in your name.

(Luke 10:17, NIV) Jesus responds by telling them, I saw Satan fall like lightning from heaven. I have given you authority to trample on snakes and scorpions and to overcome all the power of the enemy; nothing will harm you.

(Luke 10:18–19, NIV) With the context of the 70 disinherited nations in view, as well as God’s intention to reclaim those people under the rule of the wicked elohim, the meaning of this passage is clear: Jesus’ ministry is the beginning of the end for Satan and the gods of the nations.

The astute Bible student may notice that some translations record 72 disciples sent out by Jesus. Michael Heiser acknowledges this discrepancy in a footnote, where he explains that the Septuagint, the Greek Old Testament, has the number at 72. The traditional Hebrew (Masoretic) text has the number of nations as seventy. Consequently, either number points to a correlation back to the nations divided at Babel and the cosmic-geographical worldview of Deut. 32:8–9.

Heiser concludes that the Masoretic text is likely the more credible source in this case, since the number 70 corresponds to the number of council members at Ugarit. Heiser reminds the reader at this point that there is a lot of agreement among scholars that there is a direct correlation between the table of nations in Genesis 10 and the divine council at Ugarit.

The Septuagint is what Jewish people of Jesus’ day read, so it’s important to acknowledge differences among manuscripts. When the New Testament authors reference the Old Testament, they’re using the Septuagint. Though Heiser’s explanation makes sense, I wish he had devoted more space to explaining the discrepancy of the 70 versus the 72.

Israelite conquests

Many Israelite conquests were about eliminating the Nephilim bloodlines established in Genesis 6, the offspring of rival elohim. Multiple passages of the Old Testament refer to the giant clans originating with the “sons of God” coming down from heaven to human women (Genesis 6:1–4). This was true of the inhabitants of Canaan, the promised land.

For an Israelite, all this meant that the native population of Canaan had a supernaturally sinister point of origin. This wouldn’t just be a battle for land. It was a battle between Yahweh and the other gods—gods who had raised up competing human bloodlines that were opposed to Yahweh’s plan and people.

Michael S. Heiser, The Unseen Realm

Michael Heiser actually refers back to the giant clans multiple times throughout the book, as the elimination of these competing human bloodlines

is a major theme of the Old Testament. It’s just not one that modern Western Christians typically notice, perhaps due to the untenable nature of Old Testament conquests, when the Israelites would kill men, women, children, and animals—total obliteration. Heiser’s explanations are also very specific with regard to places and people groups. For a visual learner like myself, a graph of some kind would be very helpful. (Maybe I’ll add that here one day.) But a general understanding of these conquests is valuable to my personal Bible study, even if many of the details didn’t stick on my first reading.

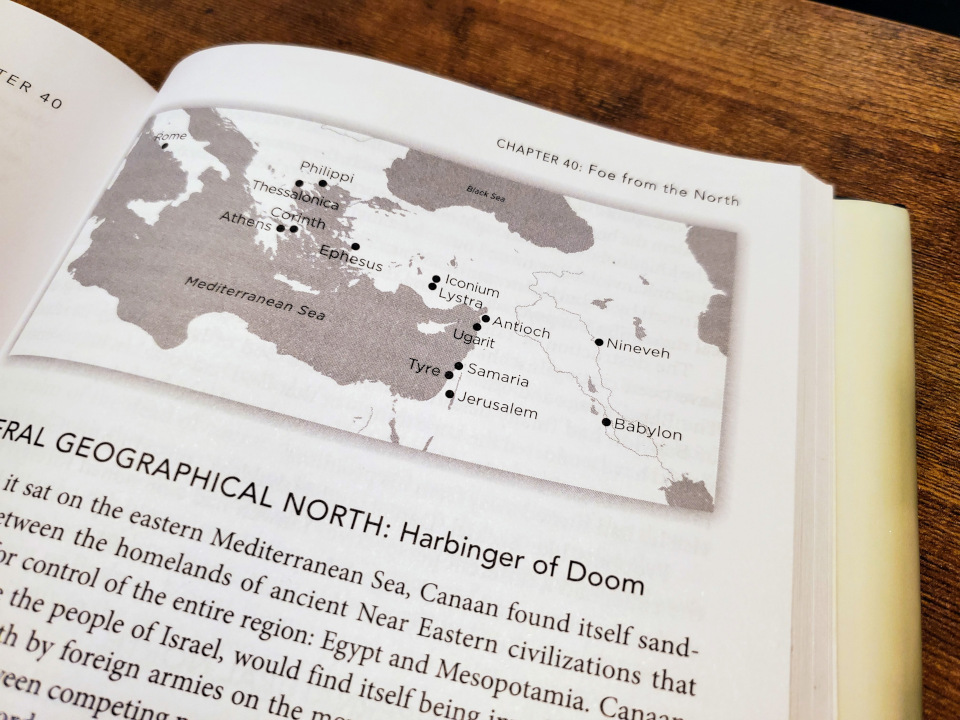

Foe from the north

For the Israelites living in the promised land, there was an ever-present psychological and supernatural dread of lands to the north.

Surrounded by enemies vying to control the land of Canaan, the Israelites were invaded from both the north and south on several occasions, but the most traumatic incursions into Canaan were always from the north.

Assyria and Babylon conquered the northern and southern Israelite kingdoms, respectively, each attacking from the north.24

The trauma of these invasions became the conceptual backdrop for descriptions of the final, eschatological judgment of the disinherited nations (Zeph 1:14–18; 2:4–15; Amos 1:13–15; Joel 3:11–12; Mic 5:15) and their divine overlords (Isa 34:1–4; Psa 82).

(Michael S. Heiser, The Unseen Realm)

Bashan is in the northern part of Canaan; it’s a place associated with the realm of the dead, giant clans like the Rephaim, and Mount Hermon, where the sons of God descended to earth to mate with human women (Genesis 6).

Beyond Bashan were Sidon, Tyre, and Ugarit, which worshiped Baal.25 According to Ugaritic mythology, Baal lived on a mountain now called Jebel al-Aqra‘ (then called Tsapanu, which is “north” in Ugaritic).26 He had many titles, one of which was zbl ba‘al ’arts (“prince, lord of the underworld”), which would eventually become Baal Zebul or Baal Zebub (Beelzebub27).

Gog and Magog

This was all part of Jewish eschatological theology because during the time of Jesus, the ten tribes of the northern kingdom were still in exile. The prophets28 had foretold that all twelve tribes of Israel would be restored, followed by the invasion of Gog, of the land of Magog

29 as described in Ezekiel 38–39 and Revelation 20:7–10. Gog will invade from the heights of the north

(Ezekiel 38:15; 39:2)—the response of supernatural evil against the messiah and his kingdom.

Heiser devotes little space to Gog and Magog in the book, but he provides other resources for further reading. Personally, I would have liked more attention on Gog and Magog, having heard theories—espoused by pastors—that Gog and Magog represent modern-day superpowers like Vladimir Putin and Russia. Heiser also points out that all eschatology is speculative and thus cannot be defined specifically.

The rider of the clouds

Would the messiah be truly divine—Yahweh incarnate—or would he be merely a man thought to be divine, by adoption? By the time of Jesus’ birth—as God incarnate—Jews were intellectually acclimated to the idea of Yahweh being (at least) in human form, including being embodied. The incarnation takes that notion another step.

Michael S. Heiser, The Unseen Realm

One of my favorite chapters in The Unseen Realm is chapter 29, titled “The Rider of the Clouds.” In this chapter, Michael Heiser explores the divine council meeting recorded in Daniel 7. The first eight verses describe a vision of Daniel’s in which four beasts, representing four empires, come out of the sea. The fourth beast is the most reprehensible and terrifying.

9 I continued watching until thrones were placed and an Ancient of Days sat; his clothing was like white snow and the hair of his head was like pure wool and his throne was a flame of fire and its wheels were burning fire. 10 A stream of fire issued forth and flowed from his presence; thousands upon thousands served him and ten thousand upon ten thousand stood before him. The judge sat, and the books were opened.

11 I continued watching then because of the noise of the boastful words of the horn who was speaking; I continued watching until the beast was slain and its body was destroyed, and it was given over to burning with fire. 12 And as for the remainder of the beasts, their dominion was taken away, but a prolongation of their life was given to them for a season and a time.

Daniel 7:9–12, LEB

Michael Heiser notes three significant points from this passage:

- The Ancient of Days is the God of Israel because of the similarities shared with the vision recorded in Ezekiel 1.

- There are many thrones, marking the appearance of the divine council.

- The council is called to decide the fate of the four beasts—to remove the dominion from three and slay the fourth beast.

The next couple of verses provide the crux of Heiser’s entire chapter.

13 I continued watching in the visions of the night, and look, with the clouds of heaven one like a son of man was coming, and he came to the Ancient of Days, and was presented before him. 14 And to him was given dominion and glory and kingship that all the peoples, the nations, and languages would serve him; his dominion is a dominion without end that will not cease, and his kingdom is one that will not be destroyed.

Daniel 7:13–14, LEB

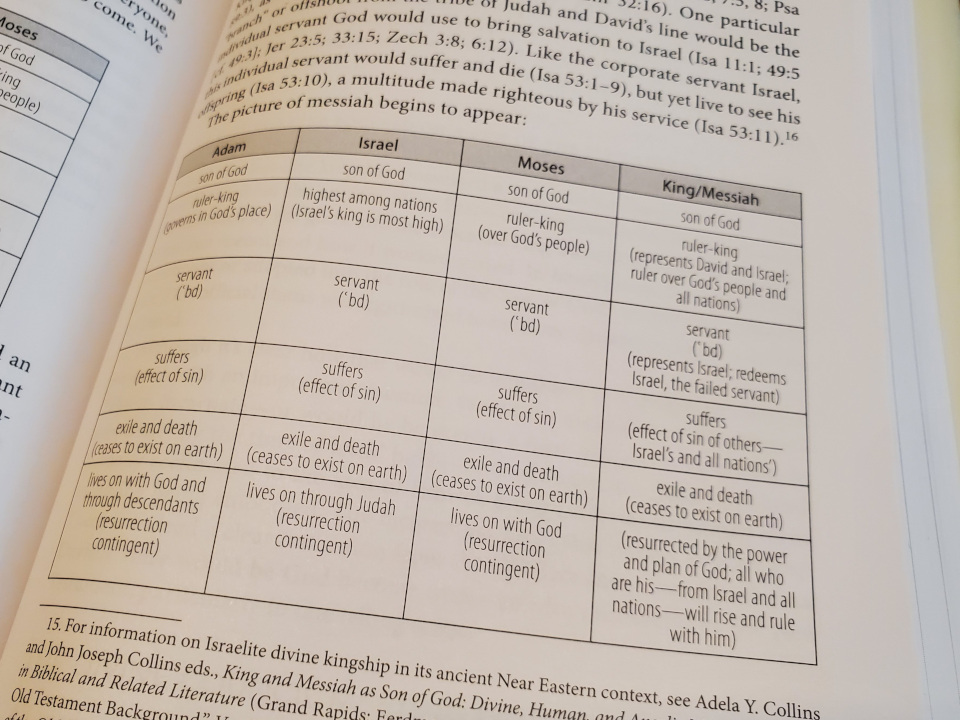

In previous chapters, Heiser describes the belief that kingship was divine in the ancient world: Civilizations believed that kingship was instituted by the gods, and therefore the king was a descendant of the gods.

For Israel, the king was adopted into the role of the

Only one Israelite dynasty had a legitimate claim of kingship, though: the line of David.son of God

to carry out Yahweh’s rule.

The Ancient of Days and the son of man are clearly different characters in Daniel’s vision, but Heiser points out that the son of man is also a deity figure.30 In the ancient Near East, Baal was called “the one who rides the clouds,” even becoming an official title. In an effort to make the point that Yahweh, the God of Israel, deserved worship instead of Baal, the biblical writers occasionally pilfered this stock description of Baal as

31 Whenever the Old Testament describes someone as riding the clouds, that someone is Yahweh; it was a theological statement that the God of Israel is the one riding clouds across the earth, not Baal. The only exception in the Old Testament is in Daniel 7:13, when the son of man is the cloud rider, receiving everlasting kingship. This is a clear indication that the “son of man” in this passage holds deity status.cloud rider

and assigned it to Yahweh.

The ultimate son of David, the messianic king, will be both human (

son of man) and deity (the rider of the clouds). That is precisely what we get in the New Testament.Michael S. Heiser, The Unseen Realm

Conclusion

There’s so much more to this book, and I hope to re-read it and make more notes. I initially borrowed a friend’s copy after he recommended it, but I picked up my own a few chapters in. This is a book that I want on my shelf to refer to when studying supernatural events in the Bible.

Michael Heiser has opened my eyes to so much of Scripture that I’ve been missing because I’ve been reading with a Western lens. What may be obvious to some people was mind-blowing to me, like multiple biblical references to the embodied Yahweh—walking and talking among his people. Prophets themselves were validated by the presence of embodied Yahweh (Adam, Moses, Joshua, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, etc.), yet I hadn’t even noticed that God interacted physically in the Old Testament.

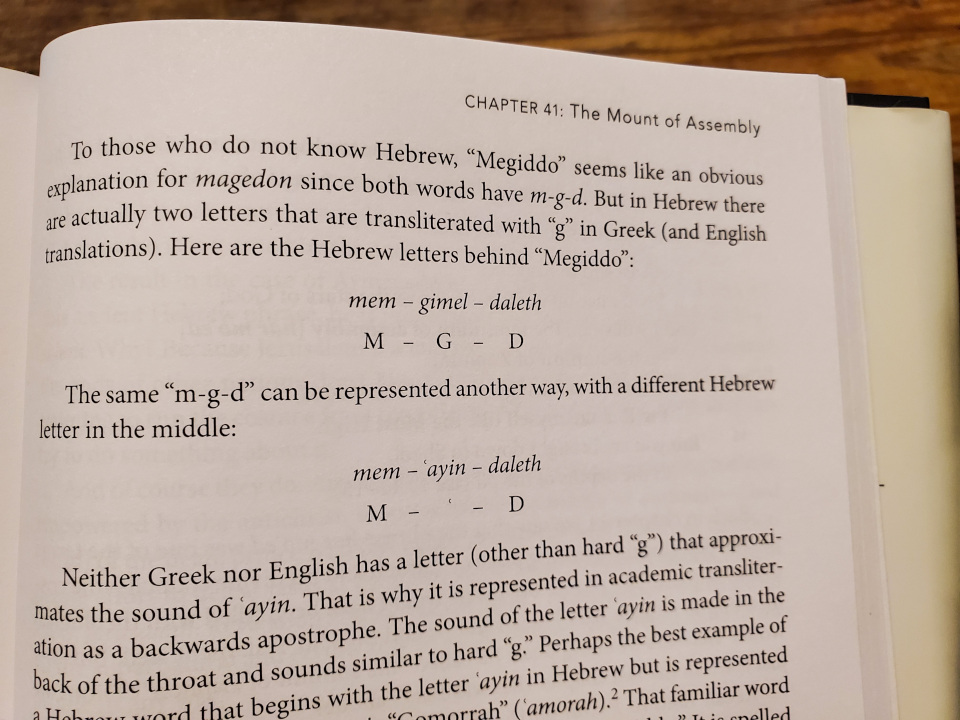

There are also several maps in sections that discuss geography, as well as charts, phonetic language guides, and helpful section summaries.

Though I cannot say I agree with everything in this book, I enjoyed it immensely as I gained a new perspective on my Creator and his history with humanity. This book review provides notes and context to help me remember some of the key points Heiser makes in the book. But I intend to re-read it, much more slowly next time. There’s so much in The Unseen Realm, and as with any theological treatise, it should be weighed and measured. I do not believe my first read wholly accomplished that for me.

Heiser ends his book with a short list of five strategies for pursuing the biblical-theological ideas that run through Scripture.

Let the Bible be what it is, and be open to the notion that what it says about the unseen realm might just be real.

The content of the Bible needs to make sense in its own context, whether or not it makes sense in ours.

How the biblical writers tie passages together for interpretation should guide our own interpretation of the Bible.

How the New Testament writers repurpose the Old Testament is critical for biblical interpretation.

Metaphorical meaning isn’t “less real” than literal meaning (however that’s defined).

The Unseen Realm is, without a doubt, the most impactful book I’ve read in 2022. The book reads like a biblical theology of supernaturalism, wherein the divine council and God’s epic plan to dwell with humanity are revealed in small and subtle ways. Michael Heiser’s careful analysis and straightforward writing have illuminated for me the nature of the spiritual forces all around us, God’s immense love for his children, and the incredible complexity and congruence of Scripture.

I can enthusiastically recommend The Unseen Realm to anyone who wishes to gain an ancient Near Eastern perspective on the Bible and challenge their own beliefs about spiritual forces.

-

The quotation of Psalm 82 by Jesus is found in John 10:34–36, but Michael Heiser omits any discussion of this passage in his book—citing “space constraints”—other than a footnote which asserts the inadequacy of most commentaries to acknowledge the divine council focal point of Psalm 82. Most commentators offer the explanation that Jesus can claim to be a son of God because every other Jew can make the same claim. In this footnote, Heiser notes that the quote in John 10 is

bookended with two suggestions of his (Jesus’) deity

: identification with the Father in John 10:30 and the assertion that the Father is in Jesus in 10:38. The reference to Psalm 82 is a way of pointing out that Scripture reveals other nonhuman sons of God, to which Jesus is superior through his relationship with the Father. ↩ -

Supernatural: What the Bible Teaches About the Unseen World—and Why It Matters (ISBN-13: 978-1577995586) ↩

-

Genesis 1:26, 3:5,22, 6:1–4, 10–11, 15:1; Exodus 3:1–14, 23:20–23; Numbers 13:32–33; Deuteronomy 32:8–9,17; Judges 6; 1 Samuel 3, 23:1–14; 1 Kings 22:1–23; 2 Kings 5:17–19; Job 1–2; Psalms 82, 68, 89; Isaiah 14:12–15; Ezekiel 28:11–19; Daniel 7; Matthew 16:13–23; John 1:1–14, 10:34–35; Romans 8:18–24, 15:24,28; 1 Corinthians 2:6–13, 5:4–5, 6:3, 10:18–22; Galatians 3:19; Ephesians 6:10–12; Hebrews 1–2; 1 Peter 3:18–22; 2 Peter 1:3–4, 2:4–5; Jude 5–7; Revelation 2:26–28, 3:21 ↩

-

Mitch Chase makes a strong case for the triune God argument in a Substack post called Let Us Make Man In Our Image: Trinitarian speech in Genesis 1:26. ↩

-

Job 1:6, 2:1; Psalm 89:5–7 ↩

-

Omnipotence itself requires a singular application. An all-powerful being holds power over every other being and cannot share that attribute with any other. ↩

-

Heiser, Michael, “Does Deuteronomy 32:17 Assume or Deny the Reality of Other Gods?” (2008). LBTS Faculty Publications and Presentations. 322. ↩

-

The Hebrew word for demon, shedim, originates from the Akkadian word shedu, which can refer to a good or evil spiritual being. The word shedim is not common in the Bible, appearing only in Deuteronomy 32:17 and Psalm 106:37. ↩

-

1 Corinthians 10:20 ↩

-

The same language appears in Isaiah 47:8 and Zephaniah 2:15, where Babylon and Ninevah, respectively, each declare

there is none besides me,

yet there were obviously other cities. Babylon and Ninevah simply considered their cities to be superior to all others. ↩ -

Walton, John H. The NIV Application Commentary: Genesis. Grand Rapids, Zondervan, 2001 (p. 130). ↩

-

John 1:14,18, 3:16,18; 1 John 4:9 ↩

-

Hebrews 11:17 ↩

-

Abraham’s first son, Ishmael, was born by Abraham’s wife’s Egyptian slave, Hagar. See Genesis 16:15 and 21:3. ↩

-

See verses 1–4 (“sons of God”). ↩

-

Friedman, Richard Elliott. Commentary on the Torah. New York City, Harper-Collins Publishers, 2001. ↩

-

Genesis 3:8ff ↩

-

In Genesis 3:14, God curses the serpent with a life of belly-crawling, eating dust

all the days of your life.

(NIV) Given this curse, it can be presumed that the opposite was true prior to the curse. ↩ -

Ezekiel 32:21,24–30,32; Isaiah 14:9 ↩

-

Genesis 9:7 ↩

-

Genesis 10 ↩

-

Luke 10:1–23 ↩

-

Assyria defeated the ten tribes of the northern kingdom in 722 BC, and Babylon conquered the two tribes of the southern kingdom, Judah and Benjamin, in three invasions (605–586 BC). ↩

-

According to Michael Heiser, and the astute Bible reader,

the fact that the center of Baal worship was just across the border was a contributing factor in the apostasy of the northern kingdom of Israel.

↩ -

The mountain of Baal was known to the Israelites as Tsaphon, which means “north” in Hebrew. ↩

-

On the New Testament use of Beelzebul/Beelzebub, see Matthew 10:25; 12:24 (cf. Mark 3:22; Luke 11:15) and Matthew 12:27 (cf. Luke 11:18–19). ↩

-

See Jeremiah 23:1–8 and Ezekiel 37:24–26. ↩

-

Ezekiel 38:1–3, 14–15) ↩

-

Throughout The Unseen Realm, Michael Heiser refers to an ancient Jewish doctrine of two good powers in heaven, similar to the Christian concept of the Trinity. He provides a resource, Two Powers in Heaven: Early Rabbinic Reports about Christianity and Gnosticism (Alan F. Segal), for further reading into the two powers doctrine, which was declared heretical by later Jewish religious authorities. ↩

-

See Deuteronomy 33:26, Psalm 68:32–33, Psalm 104:1–4, and Isaiah 19:1. ↩