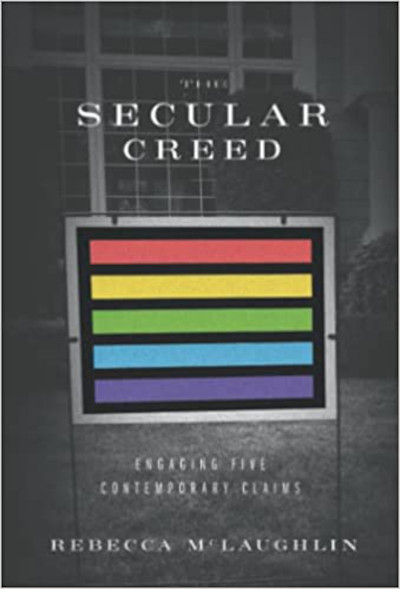

One of my favorite authors, Rebecca McLaughlin, wrote another well-reasoned (and concise) book—The Secular Creed: Engaging Five Contemporary Claims—tackling modern social issues on the doorstep of the church, if not already in the pews of many American congregations.

The book looks at five key mantras that have become increasingly popular lately—in the United States at least—appearing on signs in front yards across the country:

- Black Lives Matter

- Love is Love

- Gay Rights Are Civil Rights

- Women’s Rights Are Human Rights

- Transgender Women Are Women

McLaughlin dedicates a chapter to each key message. As with her other writings, she doesn’t approach difficult subjects like these with vitriol or defensiveness, but rather responds with love, Scripture, and reason. McLaughlin believes, as I do, that there’s nuance in these social mantras. The church should be wielding a marker instead of a mallet

when addressing the yard signs of social change.

McLaughlin begins this chapter by laying out the more noticeable American perspectives of the phrase, “Black lives matter.” She writes:

For many black Christians, it feels like an utterly self-evident truth: a claim they are tired of having to make, three words to voice centuries of anger, fear, and pain. For some white Christians, it feels like a rallying cry: a way to protest the racial injustice of which they have been keenly aware. For others, it sounds like an attack: an accusation of racism that feels unwarranted and unfair. And for still others, it feels like the spearhead of a progressive agenda: a wolf in sheep’s clothing that must be exposed.

She goes on to make the case that God created, loves, and cherishes human racial diversity. He called Abraham, a man from a city in modern-day Iraq, in order that through Abraham all people of the earth would be blessed.

Not only were the chosen people of the Old Testament dark-skinned, but McLaughlin then points out that Jesus’ own bloodline wasn’t “pure” in the way that some people might have wanted—it included Rahab the Canaanite and Ruth the Moabite. Matthew’s gospel makes this clear in what is my personal favorite genealogy of the Bible.

Even though Israel was the chosen of God, Jesus reminds his listeners in Luke 4:25–27 that God has always cared for Gentiles: both Elijah and Elisha were sent to minister to non-Israelites during difficult times—Elijah to a widow in Sidon during a great famine, and Elisha to a leper in Syria. Jesus points out that Israel had many widows and lepers during those times, yet the prophets went only to these two people. Jesus was constantly shaking up notions of inclusivity into the people of God.

McLaughlin then turns her attention to modern social justice movements, including an appropriate Christian response to those who claim we should simply “preach the gospel” and allow all societal ills to naturally heal in the wake of the gospel message, noting that Jesus did not tell his disciples to “just preach the gospel.”

Living as a disciple of Jesus includes preaching the gospel (Matt. 28:19), pursuing justice for the poor, oppressed and marginalized (Matt. 25:31–46), and practicing love across racial and cultural difference (Luke 10:25–37).

The popular belief, even among Christians, that marriage should not be restricted to the union of one man and one woman is the next issue that McLaughlin addresses. Taking a controversial approach to God’s intended design for marriage—even among Christians—she draws on the biblical theme of God’s marriage to his people. God is the husband, Israel his bride. Jesus—himself God—continues this theme by calling himself the bridegroom.

Personally, I struggled with the Bible’s depiction of homosexuality for many years before understanding the marriage metaphor of God and his people. But I am encouraged by the societal embrace of same-sex partners as deserving of dignity and respect. For far too long, they have been maligned, oppressed, and persecuted. All people are image bearers and carry the weight of that royal designation. But that doesn’t mean that God intends for same-sex attraction to be pursued.

One of my favorite points in the book is about men and women who are made in God’s image: In the Ancient Near East, this language would have signaled royalty. And in a world in which women were not seen as equal to men, Genesis specifies that female humans bear this godlike stamp.

Even when God makes the woman to be the “helper” of the man (Genesis 2:18), McLaughlin points out that this word for helper usually refers to God Himself in Scripture. What sounds subservient in English is far from it in ancient Hebrew.

Men and women are created equal and alike, but also meaningfully different from each other—and vitally different from any other animal.

McLaughlin’s conclusion sums up the key points in her book: that the church should respond to its neighbors with Christ-like love.

In a world where women are pushed into commitment-free sex, the counterculture of the church should affirm both marriage and singleness as compelling options for Christians, rather than making women who aren’t married or don’t have children feel marginalized. And against the history of shaming women for having babies outside of marriage, our churches should validate women who have chosen to keep their baby against all social pressure to abort, and offer the extended family and practical support that single mothers need.

She goes on:

If Jesus cooked for his disciples, wept with his friends, and took babies in his arms, we don’t need to pretend that manhood is just about loving cars, watching sports, and lifting weights. And if Jesus had some of his most important theological conversations with women, we must not act as if women only care about cooking and clothes. Christians must repent of the ways in which our embrace of cultural stereotypes has made some people feel as if they don’t belong in their own skin.

I greatly respect Rebecca McLaughlin for her careful writing that’s both accessible for non-academics and well-researched and noted. Though it’s not intended to answer every question or have the last word in these discussions, The Secular Creed is enlightening and acts as a great resource for five common social issues that Christians must talk about. In its few pages can be found insightful social commentary and loving concern for our neighbors.