As a marketing professor specializing in viral messaging, Jonah Berger has received many requests for a book to share the information he presents in his classes. That book is Contagious: Why Things Catch On. He describes his goal for the book as something that was rigorous but less dry than the typical jargon-laden articles published in academic journals.

Before writing Contagious, Berger found helpful books that identified viral messages, but he couldn’t find a good resource explaining how some messages race through an audience while others fall flat. But he knew word of mouth was an effective channel.

We try websites our neighbors recommend, read books our relatives praise, and vote for candidates our friends endorse. Word of mouth is the primary factor behind 20 percent to 50 percent of all purchasing decisions.

Word of mouth is more effective than traditional advertising for two main reasons: (1) It’s more persuasive, and (2) it’s more targeted. We trust the candidness of our friends, family, and neighbors, so we tend to find their endorsements more persuasive. And we typically recommend products or services to specific people based on what we know about their interests and needs. Word of mouth tends to reach people who are actually interested in the thing being discussed. No wonder customers referred by their friends spend more, shop faster, and are more profitable overall!

According to Berger, most people believe that about 50% of word of mouth happens online, but he says it’s 7% in reality. Despite the heavy cultural influence of social media and the internet, people spend most of their time offline.

Virality

In the introduction to his book, Jonah Berger tells a story of a good word-of-mouth strategy by a book publisher. Berger, a marketing professor at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, sometimes receives a free book in the mail. The publisher hopes that he will like the book enough to assign it to his classes. But a publisher once sent him two copies, along with a note asking him to pass along the second copy to a colleague. At this point, Berger himself is the marketing engine seeking out a qualified prospect for the book publisher.

The $100 cheesesteak

The story of Barclay Prime is a fascinating case study in word-of-mouth marketing. A new steakhouse in Philadelphia wanted to provide the best experience in a saturated market. Plush sofas, marble tables, and fresh delicacies wouldn’t be enough to set Barclay Prime apart, so promoter Howard Wein came up with the $100 cheesesteak—a huge price tag for a simple dish. But it was hugely successful. Not only was the cheesesteak delicious, but it provided a diner with a story to tell. Philadelphia has plenty of cheesesteaks, but for many people, seeing another cheesesteak offers them the opportunity to share their unique experience at Barclay Prime.

Will it blend?

After founding Blendtec, Tom Dickson continued to spend his days in the factory testing his blenders by attempting to blend lumber. His marketing director, George Wright, had the idea to create videos of Tom blending various objects to showcase Blendtec’s power. The videos were a hit, with the video series Will It Blend? receiving more than 300 million views on YouTube. After only two years, Blendtec’s retail blender sales had increased by 700 percent—even with a “boring” product.

The STEPPS to contagious messages

Berger spent years researching why some messages spread virally from person to person. In his research, he identified six “ingredients” that consistently show up when messages are successful. The six principles form an acronym, STEPPS, and each chapter of the book covers one of the principles.

Social currency

According to Jonah Berger, to get people talking, companies and organizations need to mint social currency. Give people a way to make themselves look good while promoting their products and ideas along the way.

The ways to accomplish this are:

- Inner remarkability

- Game mechanics

- Exclusivity

Inner remarkability

Berger opens his chapter on social currency with the origin story of a New York hot dog restaurant, Crif Dogs, with an unused liquor license. The owners acquired the space next door and installed an antique phone booth in the hot dog dining room. The phone booth is actually a secret door leading into a bar called Please Don’t Tell. The whole experience is remarkable and exclusive, especially since it only takes 30 minutes for the bar’s reservations to fill up each day.

People share remarkable stories, products, and facts because of the social currency they provide. We share the funnier jokes, the more interesting stories, and the cooler products so that people will think we are funny, interesting, and cool.

One aspect of remarkability that Jonah Berger did not mention in this section is negative remarkability, or negative word of mouth—that some brands generate a lot of word of mouth for bad reasons. Carnival cruise ships have bad service and frequent technical issues, according to some passengers. Samsung phones used to spontaneously combust and catch on fire. Dunkin’ and Starbucks have scaled back their rewards programs, leading to angry customers.

Inner remarkability is a difficult attribute to identify, much less create, in a product or service. But it can generate so much free word-of-mouth marketing.

Game mechanics

Frequent flier miles. Coffee shop punch cards. Retail app rewards. These are all examples of game mechanics, also known as gamification. Game mechanics are the elements of a game, application, or program—including rules and feedback loops—that make them fun and compelling.

A well-planned customer experience can make marketing goals fun for the customer, and even encourage social comparison.

The concept of social comparison is the reason why people share before-and-after weight loss photos, their online gaming status, gossip from the Delta Sky Lounge, and their golf score. Since people care about their performance in relation to others,

sharing these things offers a status boost while also promoting weight loss, online video games, Delta, and golf.

Exclusivity

I’m calling the third way to generate social currency exclusivity, but it’s just a way to make people feel like insiders. Berger begins this section with a story about SmartBargains.com, a website that sells offloaded retail inventory at substantial discounts. But when the website started losing traction in the market, the CEO started a new site called Rue La La, which sold the exact same products with one key difference: customers have to be invited by other members of the site in order to get access to the limited-time “flash sales” (24–48 hours), making the products scarce. Rue La La did incredibly well, and it’s all because it made customers feel like insiders with access to something special.

Alongside exclusivity is scarcity. The exclusive, secretive bar Please Don’t Tell has only 45 seats, and reservations go quickly. Disney places decades-old classic movies in the Disney Vault, making them unavailable for a while. Amazon has “lightning deals” with short lifespans and even shorter availability. McDonald’s discontinues and brings back the McRib periodically.

Exclusivity and scarcity generate word of mouth because people want to be insiders with access to knowledge and resources that others can’t get. But Berger notes that it’s possible to go too far. If it’s too difficult to get a reservation at Please Don’t Tell, people will stop trying and attendance could drop. If something is too limited then it loses its appeal to those who cannot gain access at all. Even at Please Don’t Tell, a guest receives a small card after paying for their drinks. The card reads, “Please Don’t Tell,” but includes the bar’s phone number.

Berger ends his chapter on social currency with a note about motivation. He believes that social currency is more powerful than monetary rewards. People will share and refer what they find to be remarkable and exclusive, but as soon as you pay people for doing something, you crowd out their intrinsic motivation.

Social incentives, like social currency, are more effective [than money] in the long term. Foursquare doesn’t pay users to check into bars, and airlines don’t give discounts to frequent flier members. But by harnessing people’s desire to look good to others, their customers did these things anyway—and spread word of mouth for free.

Triggers

Jonah Berger opens this chapter on triggers by comparing Walt Disney World with Honey Nut Cheerios—one exciting brand and one fairly dull brand. Intuitively, most people would expect Disney World to achieve more word of mouth than Honey Nut Cheerios, but Berger says that’s not the case. In studies of thousands of product conversations, Berger and his team discovered that the frequency of word of mouth is mostly equal between interesting and boring brands—until they asked a different question.

We had been focused on whether certain aspects matter—specifically, whether more interesting, novel, or surprising products get talked about more. But as we soon realized, we also should have been examining when they matter.

Immediate and ongoing word of mouth

Berger and his team soon identified two types of word-of-mouth frequency: immediate and ongoing. Immediate word of mouth gets talked about soon after the experience—within a few hours or days—whereas ongoing word of mouth happens several weeks, months, or years later. Interesting products tend to generate more immediate word of mouth than boring products. That makes sense. But what’s surprising is that interesting products generally cannot sustain high levels of ongoing word of mouth.

Environmental stimuli

That brings Berger to the subject of his chapter: triggers. Environmental stimuli can affect purchase behavior in ways that make so much sense once you stop to think about it. Hearing a car engine sputter can make you remember that yours is due for an oil change. Smelling pizza can make you think of dinner. Advertisements themselves act as triggers.

Some product triggers are unintentional, and others are manufactured. Mars, the candy company named after its founder, saw an uptick in sales in mid-1997 around the time of NASA’s Pathfinder mission to the planet Mars. Music researchers successfully altered wine purchases by playing different music in the grocery store—French music led to more French wine purchases, and German music generated more sales of German wine.

Influencing healthy eating

Working with psychologist Gráinne Fitzsimons, Berger studied healthy eating among college students. They paid the students to simply report on their diet for two weeks, but one week in, they invited the students into a seemingly unrelated focus group to choose a healthy slogan from the following:

Live the healthy way, eat five fruits and veggies a day.

Each and every dining-hall tray needs five fruits and veggies a day.

The students overwhelmingly preferred the first slogan, calling the second one “corny” and unlikely to influence their own consumption of fruits and vegetables. But students who had seen the ‘tray’ slogan and used trays in their cafeterias markedly changed their behavior. The trays reminded them of the slogan and they ate 25 percent more fruits and vegetables as a result.

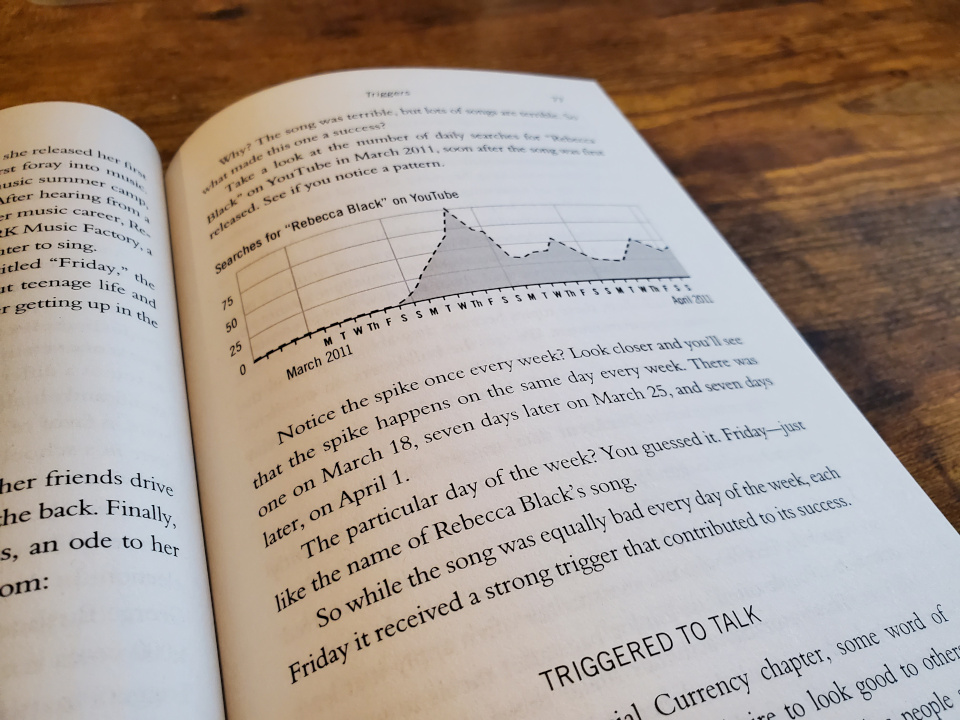

Triggers can be powerful influencers of behavior. Studies have shown that political votes cast from inside school buildings achieved results more favorable for school districts, even after controlling for regional and demographic factors. And the 2011 self-produced song “Friday,” by Rebecca Black, achieved more than 300 million YouTube views, with spikes every Friday during its popular streak. The whiny, overproduced number about teenage life and the joys of the weekend

was triggered in people’s memories every Friday.

Top of mind means tip of tongue.

Small talk is the most common type of communication, and it is often the catalyst for triggered word of mouth. We fill the empty space of our conversations based on what’s going on around us. When it comes to products, Berger found that more frequently triggered products got 15 percent more word of mouth.

And triggers generate higher levels of both immediate and ongoing word of mouth.

Consider the context, grow the habitat

GEICO failed to use triggers in its caveman commercials (“It’s so easy a caveman could do it.”), but Budweiser nailed it with their “Whassup?” commercials. Where GEICO failed, Budweiser succeeded by considering the context and using a common male greeting (at the time). Whenever guys greeted each other that way, they couldn’t help but think of beer.

In the same way, it’s important to consider the context of a marketing campaign. Are there natural triggers that can bring the brand to mind? What kinds of associations can be made between a brand and existing environmental triggers? That’s what Kit Kat needed to find out back in 2007.

After more than twenty years of the “give me a break” jingle getting stuck in consumers’ heads, Kit Kat needed a new marketing campaign. Sales had been declining year after year, and the shrinking brand couldn’t spend top dollars on TV commercials. But market research uncovered that consumers frequently enjoyed Kit Kit bars (1) on breaks and (2) with a hot beverage. And so Kit Kat was paired with coffee in radio spots and soon became known as “a break’s best friend.” By associating Kit Kat with coffee, the company grew the brand’s habitat. Coffee had become a trigger for people to enjoy a Kit Kat. With the abundance of coffee triggers in American life, the Kit Kat brand soon grew from $300 million to $500 million.

Biologists often talk about plants and animals as having habitats, natural environments that contain all necessary elements for sustaining an organism’s life… Products and ideas also have habitats, or sets of triggers that cause people to think about them.

The poison parasite

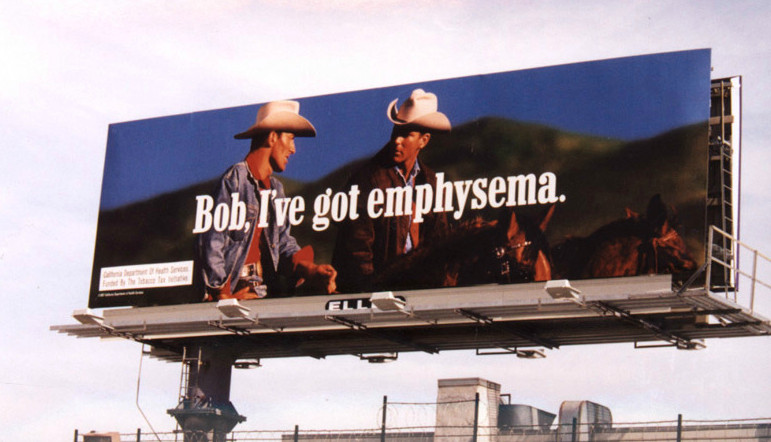

In a clever anti-smoking campaign, the famous Marlboro cowboys can be seen on a billboard with big words emblazoned over them reading, “Bob, I’ve got emphysema.”

This use of triggers by a competitor is called the poison parasite—when a brand injects its message into a competitor’s message, turning the rival into a trigger for its own brand.

What makes an effective trigger?

So what makes an effective marketing trigger? Berger points out three key features: frequency, strength, and proximity. A good trigger occurs frequently in the brand’s environment, has a strong connection to the brand or idea, and is within or near the brand’s habitat. All of these features together can make a great trigger for your brand or idea.

Emotion

Berger opens his chapter on emotion with a story about a science journalist at The New York Times who wrote a viral article in 2008. The journalist, Denise Grady, wrote about the use of a special photography shot called the schlieren technique to study coughing visibly. But Grady had no idea why her article was shared so excessively.

Years later, Berger and his team of researchers were able to pinpoint the reason. After studying virality among The New York Times articles, they had found that many viral articles were shared because they were either interesting (social currency) or useful (practical value). But Berger didn’t believe that either of those reasons really fit with this medical research article—or any viral science article.

It turns out that science articles frequently chronicle innovations and discoveries that evoke a particular emotion in readers. That emotion? Awe.

Awe is what takes your breath away when you see something incredible, like the Grand Canyon, or hear a beautiful voice, like that of Susan Boyle during her audition on Britain’s Got Talent. And Berger found that awe is one of the most powerful emotions when it comes to virality.

Physiological arousal

There are more emotions that encourage people to share. Berger refers to emotion sharing as “social glue” that strengthens relationships. Sharing content builds bonds between people. We share awe-inspiring videos, funny memes, and infuriating news with friends, which reminds us of how much we have in common.

But not every emotion encourages sharing to the extent that awe does. Sadder articles were 16% less likely to be shared than articles that induce awe. And contentment, while a good feeling, also encourages less sharing than emotions like awe, amusement, and anger. Some emotions—awe, contentment, excitement, and amusement—are considered positive, while others—anger, anxiety, sadness—are negative. But there is a second dimension used to categorize emotions: physiological arousal.

Physiological arousal describes the association between an emotion and the response it evokes. High arousal emotions encourage active reactions and sharing. Low arousal emotions promote passive responses and less sharing.

| High arousal | Low arousal | |

|---|---|---|

| Positive | Awe Excitement Amusement (humor) |

Contentment |

| Negative | Anger Anxiety |

Sadness |

The positive and negative categories of high and low arousal start to make sense when you consider how you typically respond to these emotions. Contentment, while a good feeling, doesn’t create any urgency whatsoever. The same is true for sadness; when we’re sad, we tend to isolate and not do much. On the other hand, the high arousal emotions evoke responses that typically lead to action.

Berger notes the power of physiological arousal by sharing a story of United Airlines breaking a musician’s guitar and refusing to compensate him. After months of negotiating with United to no avail, musician Dave Carroll uploaded a video to YouTube titled “United Breaks Guitars” (July 6, 2009). Within four days of the video being posted, United’s stock price fell by 10% ($180 million). Beyond the financial hit, United suffered a lot of bad PR—the video was one of the most viral videos of 2009—all because of Dave Carroll’s anger toward United Airlines.

Physiological arousal increases sharing even when the source of arousal isn’t emotional, but physical. Jonah Berger and his team studied participants who were presented with an article and given the opportunity to email it to someone after reading it. But half of the study participants were asked to jog in place for sixty seconds before reading the article, while the other half relaxed in their chairs for the same amount of time. The jogging group shared the article at more than twice the rate of the relaxing group, leading Berger to conclude that any physiological arousal, whether emotional or physical, can encourage people to share.

Focus on feelings

The main message of this chapter can be summed up in three words: focus on feelings. Many ads focus on facts, but the better strategy employs emotion. Rather than harping on features or facts, we need to focus on feelings; the underlying emotions that motivate people to action.

Unlike United Airlines, Googler Anthony Cafaro understood the power of emotions when he came up with his “Parisian Love” campaign to promote Google Search. In the straightforward and logical world of internet search engines, Google produced a viral hit by focusing on feelings.

Public

Berger uses many examples in his chapter on public visibility—from Apple deciding on the direction of the logo on a laptop, to identical gyro carts in New York City with vastly different line lengths, to public health campaigns voicing people’s true feelings. All of these campaigns were made successful by embracing a key idea: the more a behavior can be seen, the more it can be imitated. If something is built to show, it’s built to grow.

Behavioral residue

In 2003, at the height of Lance Armstrong’s career, the Livestrong wristbands were released to raise awareness and funds for the Lance Armstrong Foundation (now the Livestrong Foundation). After briefly commenting on the performance-enhancing drugs that tainted Armstrong’s career, Berger notes that the massive success of the Livestrong campaign was due, not only to the public visibility of Lance Armstrong himself, but to the persistence of the wristbands in a person’s everyday life—something Berger calls behavioral residue.

Behavioral residue is the physical traces or remnants that most actions or behaviors leave in their wake. Mystery lovers have shelves full of mystery novels. Politicos frame photos of themselves shaking hands with famous politicians. Runners have trophies, T-shirts, or medals from participating in 5Ks.

If the alternative to the Livestrong wristbands—a bike ride across America—had been chosen instead, the interest in Armstrong’s foundation likely would have waned. But the wristbands kept his foundation top-of-mind long after their release.

Make the private public

When the private becomes public, people can feel more comfortable voicing their opinions and beliefs. Online dating is one example. Many people have tried online dating, but there remains a social stigma, so a lot of people don’t realize how many of their friends have also tried online dating.

The Movember Foundation raises awareness of prostate cancer by encouraging men to grow mustaches in November. Some men raise money; others just raise awareness. But a previously private health concern now receives more funding after being made public in a memorable and fun way.

The message of public visibility is really about making ideal behaviors observable, and thus imitative. It’s been said that when people are free to do as they please, they usually imitate one another.

Make products that advertise themselves. Create behavioral residue. Bring the private out into the public space.

Practical value

Jonah Berger opens his chapter on practical value with a story of an 86-year-old corn farmer from Oklahoma. After years of eating corn, Ken Craig had figured out a way to shuck an ear of corn without leaving behind corn silk. A common problem when shucking corn yourself, corn silk is the thin, threadlike fibers that cling to the cob. But in Ken Craig’s viral video, he shares how to quickly shuck an ear of corn, leaving it “clean as a whistle.”

Berger presents this example of virality as a lesson in offering practical value. It could be argued that emotion is a factor—Ken is a kind, grandfatherly figure—or perhaps the social currency of a mildly interesting way to clean an ear of corn. But the strongest factor here is that the video offers practical value for corn lovers. In less than two minutes, Ken succinctly explains his simple method, and viewers have found it useful.

Why share practical information?

People share practical information in order to be helpful. While social currency is more about the communication sender, practical value is mostly about the communication receiver. The sender can still get social currency from sharing practical information, but the driving force behind practical value sharing is the intent to provide someone with useful information.

In another example, Berger recounts a hike he shared with his brother. They were behind another group, close enough to overhear a conversation about vacuum cleaners. Despite the poor social currency and emotion associated with vacuum cleaners, and the sheer lack of triggers in the middle of the woods, the group of hikers was deep in conversation. Why? The answer is simple. People like to pass along practical, useful information. News others can use.

Diminishing sensitivity

To describe a concept called diminishing sensitivity, Berger uses an analogy about purchasing a clock and a television. Given the retail price of each item—$35 for the clock, $650 for the television—most people would drive twenty minutes to save $10 on the same clock elsewhere, yet the numbers are reversed when it comes to saving $10 on the same TV.

| Product | First price | Second price | Savings (%) | Would buy at first price |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clock | $35 | $25 | 29% | 17% |

| Television | $650 | $640 | 1.5% | 87% |

Diminishing sensitivity reflects the idea that the same change has a smaller impact the farther it is from the reference point.

This is why most people would go out of their way to save $10 when it’s nearly 30% of the price, but won’t do the same to save $10 when it’s less than 2% of the price. When you think about it, this makes so much sense. It just doesn’t seem worth my time to inconvenience myself to save 1.5%, but if I can drive twenty minutes to save 29% I’ll do it. In situations where the cost savings are small percentages, it’s best to communicate dollar amounts.

Narrow the specificity of content

Why does some useful content get shared more often? The reasons, says Berger, are because of simple information packaging and well-defined audiences.

Information packaging should be simple to make it easy to understand the practical value quickly. The most popular headlines, when it comes to practical value, tend to be listicles—articles in the form of a list (e.g. “10 Best Vacation Books” or “7 Healthy Snacks to Try”). And good email newsletters don’t have twenty-five stories; they have one main article and two or three minor featured stories. When in doubt, KISS: “keep it simple, stupid.” (Not from the book.)

When it comes to choosing an audience for practical value content, it might seem like a broader audience will resonate with more people. Maybe. But the more likely scenario, according to Jonah Berger’s research, is that narrower content gets shared more. Why? Because unique content is more likely to remind a reader of a specific friend for whom that content is extremely relevant. We feel compelled to share useful information with that one person who will likely act on it.

Of the six principles of contagiousness that we discuss in the book, Practical Value may be the easiest to apply. Some products and ideas already have lots of Social Currency, but to build it into a video for a blender takes some energy and creativity. Figuring out how to create Triggers also requires some effort, as does evoking emotion. But finding Practical Value isn’t hard. Almost every product or idea imaginable has something useful about it. Whether it saves people money, makes them happier, improves health, or saves them time, all of these things are news you can use.

Stories

Berger begins his chapter on stories with one of the most famous Greek epics in history: the Trojan horse. Noting that Homer and Virgil could easily have gotten right to the point—never trust an enemy—he says that wrapping the lesson in a story makes it more memorable and effective to readers.

By encasing the lesson in a story, these early writers ensured that it would be passed along—and perhaps even be believed more wholeheartedly than if the lesson’s words were spoken simply and plainly. That’s because people don’t think in terms of information. They think in terms of narratives. But while people focus on the story itself, information comes along for the ride.

Berger makes the case that people are less likely to argue against stories than against advertising claims.

He gives two reasons: (1) it’s hard to argue with the experience of another person, and (2) stories invite engagement, which uses cognitive resources. We don’t have the cognitive resources to disagree.

It’s fitting that the sixth and final principle of virality is storytelling since Berger has devoted so much of his book to anecdotes and interesting stories. In fact, you could get the major bullet points of Berger’s book from this book review—or even from the book’s table of contents—but for the messages to really sink in and stick with you, you have to read the book itself. You have to experience the author’s own storytelling.

Conclusion

Contagious is a well-written and engaging book that provides valuable insights into the psychology of social influence. It’s a must-read for anyone who wants to understand why certain things catch on and others don’t. I found the examples that Berger uses to illustrate his principles to be very helpful. They make the concepts more concrete and easier to remember.

I also appreciated the practical advice that Berger provides. He gives clear and actionable steps that anyone can take to increase the chances of their ideas going viral.

I read this book with my marketing team. We spent an hour every week discussing one chapter, which I found to be a very helpful way to dissect the ideas in the book and brainstorm new ways to promote our own products. Contagious is a relatively short book with plenty of interesting stories to keep it from being a dry how-to marketing book. I recommend Contagious for anyone with an idea to promote.